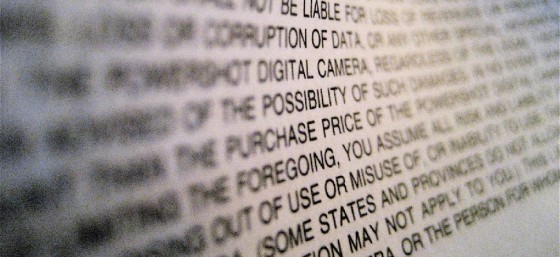

When a lawyer writes a contract for a client, it usually includes provisions that say that the all the terms of the agreement are contained in the document and all changes to the contract must be in writing. It may look something like this:

This Agreement is the entire understanding between the Parties concerning the subject of this Agreement. This Agreement replaces and supersedes any and all prior oral or written agreements and discussions between the Parties on that subject. All amendments to this Agreement must be in writing and signed by the Parties.

Contracts are relationship management documents. They keep everyone on the same page to prevent problems down the line or to help resolve problems when they occur. One of the challenges I encounter with contract clients is they often don’t follow the contract they signed and amend the agreement that is documented only in an email exchange, or worse, a undocumented verbal agreement.

Always Get It In Writing

The purpose of the “entire agreement” clause is to put all the terms of the contract in a single document. All written amendments should be stored with the original agreement – in hard copy and/or electronically, so if there is a question or dispute, the parties only need to review the single or amended document. They don’t have to piece together the contract from the parties’ communications and actions.

If you don’t get your amendments in writing, you’re asking for trouble. There could be confusion about what the change is, or worse, the other side could deny the existence of an amendment and screw you over. Remember, the law does not care about what you know, only what you can prove. If you don’t get your amendments in writing, and you have an “entire agreement” clause, if you have to go to court, the judge could say the amendment doesn’t exist.

Contract Amendments Can Be Easy

Why don’t people put their contract amendments in writing. I suspect it’s because they think it will be a hassle, cause a delay in a project, be time-consuming, or maybe they don’t even think to put in it writing because “it’s not a big deal.” In general, contracts exist, not for when things go right, but when they go wrong. What you think is a minor verbal change when both sides are getting along can become a big problem if things turn sour.

If you spend $100s or $1,000s to have a lawyer draft your contract, don’t revise it without their involvement. You’ve invested time and money to protect your interests. You don’t want to inadvertently throw that away with a damaging and undocumented revision.

Contracts are your Friends

These are some of my guidelines when it comes to reading and drafting contracts:

- Never sign a contract you don’t understand. Don’t be afraid to ask for clarification.

- Whomever writes a contract does so for their or their client’s benefit. Keep that in mind when a contract is written by the other side. (Lawyers have an obligation to represent their clients zealously.)

- Substantial business contracts should always be reviewed by a lawyer to ensure it’s complete and protects your interests.

A contract should be written to protect everyone involved – to make sure everyone understands and agrees to the same course of action.

I’m constantly reviewing and drafting all types of contracts for clients. If you want to keep up with what I’m doing or if you need help, you can contact me directly or connect with me on Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, or LinkedIn. You can also get access to more exclusive content that is available only to people on my mailing list, by subscribing here.