I’ve been on my soapbox for a while about the importance of registering your trademark if you have a blog. Even if your following is small, you want to stake a claim to your site’s name because if someone registers your name before you, they can essentially shut down your site. If they register your name as a trademark after you’ve started your site, you don’t have to shut down your site, but you can’t grow you market.

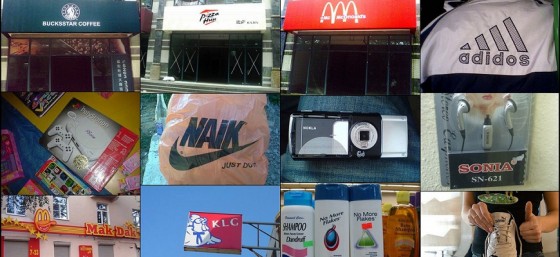

This is not a new problem but it is getting more complicated in the online world. The most infamous trademark story I know in the brick-and-mortar world is about two different Burger King restaurants. The most infamous situation in the blogosphere is the Turner Barr situation:

When I speak at social media and blogging conferences, I encourage everyone who has a blog to register their site’s trademark with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). (Ditto for vlogs and podcasts.) A lot of people agree that it’s a good idea; however most people don’t follow through and do it.

The #1 reason I hear why most people don’t register their trademark: the cost.

I’m not going to lie. Registering a trademark is expensive. The filing fee alone is at least $225. But what would suck more – paying for a trademark or having to rebrand because someone else registered it – especially if your plans include making money off your site?

I am almost through the process of registering the trademark for my blog, The Undeniable Ruth. It’s got me thinking that I could do small workshops with bloggers (3-5 participants) that includes an overview of trademarks and then I could lead them through the process of filling out the USPTO trademark application during the session, and then shepherd their applications through the rest of the process. Since it would be in a group setting, I could charge half the price of what I’d normally charge to submit an application for a client (only $499 instead of $1,000).

If you want to know more about the legalities of blogging, please watch my Q&A keynote from TechPhx or check out my book The Legal Side of Blogging: How Not to get Sued, Fired, Arrested, or Killed. You can also contact me directly or connect with me on Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, or LinkedIn.